Why is Chhattisgarh turning into an Elephant Graveyard?

Raipur | Correspondent: Report by the Wildlife Institute of India reveals that Chhattisgarh State is home to only one percent of India’s elephant population.

Despite that, a worrying data shows that 15 percent of all human-elephant conflict-related deaths in the country occur in Chhattisgarh.

Noteworthy issue here is that still after more than two decades of elephant presence in the State, both political leaders and majority of forest officials are reluctant to acknowledge that these elephants are permanent residents of the state. Thus, lacking the vision and management practices for the proper conservation of the National Heritage Animal, elephants.

Officials often downplay the situation by claiming that the elephants have migrated from neighbouring Odisha and Jharkhand.

Notwithstanding these claims, there is substantial evidence of wild elephants breeding in the Chhattisgarh Forest from last two decades and inhabiting Chhattisgarh for over a thousand years.

Ain-e-Akbari to Tripuri

Historical references include mentions of elephants in the 11th-century copper plate of Madhurantak Dev in Rajpur, Bastar.

Additionally, Abul-Fazl’s ‘Ain-e-Akbari’ notes the presence of elephants in Bastar, Sarguja, and Ratanpur.

During the Mughal era, the Kalachuri kings of Chhattisgarh were known to keep and gift elephants.

Captain J. Forsyth’s ‘Highlands of Central India’ (1981) and A.A. Dunbar Brander’s ‘Wild Animals in Central India’ (1923) also documented the presence of elephants in the region.

Forsyth, who visited the Bilaspur area of Chhattisgarh in 1860, was even tasked with creating a plan to control the crop damage by elephants.

A.E. Nelson’s ‘Bilaspur Gazetteer’ raised concerns about the declining number of elephants in the forests of Uproda and Matin.

Reports from 1930 also detail the capture of wild elephants in Bilaspur.

During the 52nd session of the Indian National Congress in Tripuri, Jabalpur in 1939, the Maharaja of Surguja sent 52 elephants to the convention, highlighting the continued presence of elephants in the region.

However, post-independence, sightings of elephants became sporadic.

Elephant from undivided Bihar

According to forest department documents, in 1988—12 years before Chhattisgarh became a separate state—a herd of 18 elephants entered Sarguja from undivided Bihar.

Then, Forest Department of MP decided to capture this herd of 18 elephants to manage the Human Elephant Conflict, which was not very successful, as in that operation 13 elephants being captured and 5 died during this operation.

The state government appointed the famous Mahawat Parvati Barua from Assam to capture the elephants in Surguja, as forest officials in MP has no experience of dealing with the wild elephants.

Mike Pandey made documentary of this whole operation and won the Green Oscar for his film “The last Migration” which is the first Green Oscar in Asia.

He later created another film on the same Elephant Capture Operation titled ‘Vanishing Giants’, which leads to policy changes in the Central Government for the Elephant Conservation in the country.

Elephant Conflict

Initially, after Chhattisgarh became a separate state, only four districts—Sarguja, Jashpur, Raigarh, and Korba—were affected by elephants, with human-elephant conflicts limited to these areas.

However, the issue has since escalated, now impacting most areas of the state, from Sarguja to Bastar.

The elephant population has continued to grow, and today, at least 550 elephants are permanently residing in Chhattisgarh

When Chhattisgarh became a separate state in 2000-2001, that year, only two people were killed in elephant attacks one in Korba and the other in Raigarh.

However, by 2022-2023, this number had risen dramatically, with 74 people losing their lives to elephant attacks.

In 2000-2001, there were 21 reported cases of crop damage caused by elephants, all of which were from Korba district.

Nearly two decades later, in 2019-2020, this figure skyrocketed to 20,424 cases.

Elephant graveyard

In 2001-2002, only one elephant was killed in Balabhadranagar, Raigarh.

Fast forward to 2022-2023, Chhattisgarh turned to be an elephant graveyard recording 23 elephants that died in the state, averaging nearly two deaths per month.

The territory of elephants has now expanded from Surguja to Bastar.

The forest department has shown their insensitivity in scientifically managing with vision of landscape level conservation for elephants and also dealing with the human elephant conflict (HEC).

Unsympathetic and thick-skinned forest officers

In the areas where the forest department once distributed compensation for a thousand cases of crop damage in a year due to elephants.

The corrupt officers later gave NOC for the coal mining, falsely stating that ‘यहां हाथी यदा-कदा आते हैं’ – ‘elephants occasionally visit these areas.’

As a result, Coal mining opened one after the another resulting in the fragmentation of habitats and corridors of the gentle giants, resulting in increase in HEC and Elephants deaths.

Although Sarguja Elephant Reserve and Lemru Elephant Reserve were established but one can understand the seriousness and vision of State Forest Department, as yet, there is no proper vision document and plan or the landscape management body even between the neighbouring districts including all concerning Government Departments.

There is no convergence plan to deal with the conflict in the field.

For instance, Lemru Elephant Reserve still lacks a director or deputy director. The post is still not created, forget about any dedicated IFS Officer in field just for elephants.

The relentless push for mining has made the situation worse.

The Hasdeo Aranya region, covering Sarguja and Korba, was once declared a ‘NO-GO Area’ by the central government due to its rich ecological value.

A joint study by Coal Ministry and MoEF&CC identified it as the only area in the country where mining would be eco-hazardous.

Despite this, Adani’s first MDO based coal mine, ‘Parsa East Kete Basan,’ was approved, leading to a series of approvals of other coal blocks in the vicinity.

Initially, it was claimed that coal mining in Hasdeo Aranya was crucial for providing electricity to Rajasthan.

But even after meeting that need, greed of new coal blocks are not coming to an end.

Rajasthan’s coal requirement: A reality check

Rajasthan’s maximum annual coal requirement for power generation is 21 million tonnes.

The operational PEKB mine in the Hasdeo Aranya, which is already allocated to Rajasthan, has the capacity to fulfil their requirement of coal every year.

The Central Electricity Authority (CEA), a Government of India institution, establishes the criteria for determining coal consumption based on the unit size of various power plants.

According to CEA’s order No. 219/GC/BO/TPPD/CEA/2021/224, issued on July 20, 2021, Rajasthan’s total annual coal requirement, based on maximum operational capacity (85%), is 21 million tonnes.

राजस्थान के पावर प्लांट, जहां हसदेव से कोयला जाना है

| पावर प्लांट | यूनिट नंबर | हसदेव के कोल ब्लॉक से लिंक क्षमता |

|---|---|---|

| छाबड़ा पावर स्टेशन | 3 व 4, प्रत्येक 250 MW | 500 MW |

| छाबड़ा पावर स्टेशन | 5 व 6, प्रत्येक 660 MW | 1320 MW |

| कालीसिंध पावर स्टेशन | 1 व 2, प्रत्येक 600 MW | 1200 MW |

| सूरतगढ़ पावर स्टेशन | 7 व 8, प्रत्येक 660 MW | 1320 MW |

| कुल | 4340 MW |

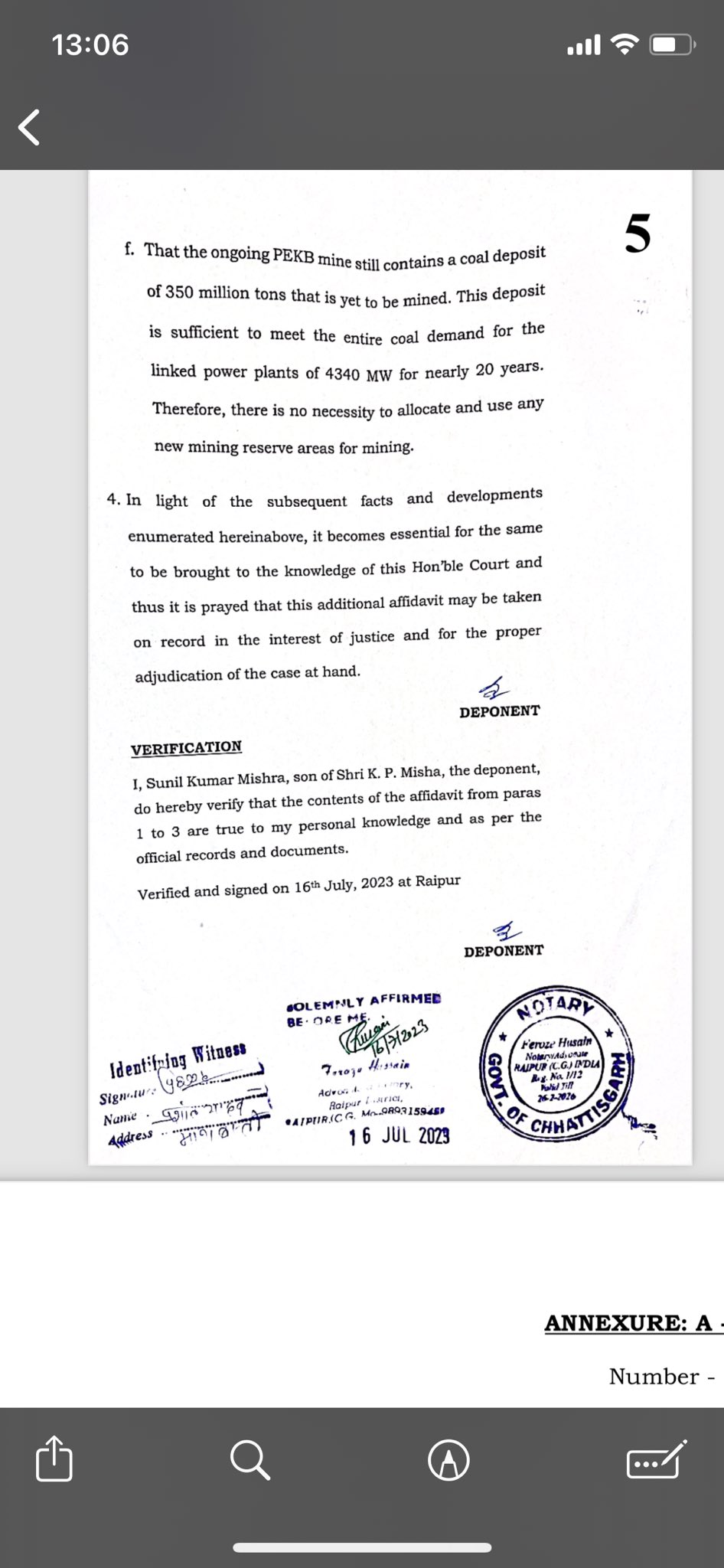

The Chhattisgarh government submitted an affidavit to the Supreme Court on 16 July 2023.

This affidavit stats that 350 million tonnes of coal deposit, remains to be excavated in the Parsa East Kete Basan mine, where mining activities are already underway.

The Chhattisgarh government has clearly stated in its affidavit that Rajasthan’s requirement of 4340 MW can be met from this single coal block (existing mining) for the next 20 years.

Adani’s share of Rajasthan’s coal supply

Recent data reveals that within a year, the Adani Group transported approximately 3 million tonnes of coal from PEKB mine allotted to Rajasthan to fuel its own power plant and other industries.

In 2021, Adani Group dispatched 49,229 wagons of coal from this mine to various destinations, with 39,345 wagons sent directly to its Raipur power plant.

The Adani Group has an agreement with the Rajasthan government allowing it to use coal from this Rajasthan-allotted mine for its Raipur power plant, but the electricity generated by this power plant is not for Chhattisgarh.

Currently, the Adani Group is advancing to the second phase of excavation from this mine.

However, this phase requires the felling of at least 2,22,921 trees from the dense Hasdeo forest, a figure that is likely outdated as the number of trees has since then increased.

Meanwhile, tribal communities and affected villagers from this area are actively opposing the Parsa and Kete Extension mines, claiming that the approvals for these projects were obtained illegally.

Overlooked warnings

Two years ago, a study by the Wildlife Institute of India, commissioned by the Supreme Court, warned of severe human-elephant conflicts if even a single new mine were to be opened in the Hasdeo Aranya region.

In its report, the Wildlife Institute of India mentioned – “The coal mines along with the associated infrastructure development would result in loss and fragmentation of habitat. Mitigating such effects on wildlife, particularly the animals with large home ranges such as elephants is seldom possible.

The human-elephant conflict in the state is already acute and has been escalating with huge social and economic costs on the marginal, indigenous local communities. Any further threat to elephants’ intact habitats in this landscape could potentially deflect human-elephant conflict into other newer areas in the state, where conflict mitigation would be impossible for the state to manage. Opening up of the demarcated coal blocks in the HACF would compromise the imperatives of biodiversity conservation and livelihood of forest-dependent local communities. Even the effects of the operational mines of PEKB and Chotia need to be tactfully mitigated too, wherever possible.”

However, these warnings are being ignored, and new mines continue to be approved.

The state government has greenlit the Parsa and Kete extension projects.

As a result, the prospect of escalating human-elephant conflict in Chhattisgarh looms large.

Is anyone truly ready to confront the reality of the imminent conflict that lies ahead?